Posted By: Mark

Posted on: 2011-01-15 22:49:21

Featured Item:

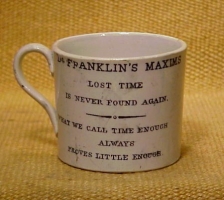

Juvenile Wares Featuring Franklin's Maxims

Early in my adult life, I began to suspect that I had grown up in a world a little closer to the nineteenth century than others. One of the features of my education (probably no mandate of the Indiana Board of Education), had to do with what were called "little sayings." These tasty little tenets were spoon fed to us in Junior High in preparation for navigating the rougher seas of life.

Given that background, as we pondered a new year in these somewhat uncertain times, it only seemed natural to fall back on the familiar. So for this month's featured item, we take a look at the collected wisdom of the original American sage and entrepreneur, Benjamin Franklin.

One caution: we have tinkered a bit with our usual "featured Item" format to consider the whole category of Franklin's Maxims decoration on motto plates and mugs. Seekers currently offers seven examples of "Franklin's Maxims" which we have used to illustrate our text. Links to the detailed listings for these items accompany each photo. These are conveniently included with ABC plates under the "Juvenile & A-B-C Plates" category on the Seekers Antiques website, www.seekersantiques.com.

Franklin's Maxims

The "Franklin's Maxims" monicker covers an entire category of transferware motto plates and mugs, each decorated around one or two little sayings. Invariably produced on earthenware, these pieces accompany the maxim(s) with an illustrative scene executed in transfer. Some sort of decorative molded border finishes the plates--somtimes an alphabet, other times a floral field or even a single spray. Enamel highlighting often enlivens the center scene and/or border while occasional touches of lustre add a bit of glitter.

The Wares -- A Salute to the Cheap and Cheerful

Any in-depth discussion of these wares soon runs aground on the "Juvenile/ABC" label usually assigned to them for the sake of convenience. This is not an illogical conclusion as many of these pieces carry a molded alphabet border and often depict scenes and sentiments directed to children. However the Franklin's Maxims wares can also be viewed as part of a larger group of subjects appearing on molded edge plates that appeal to adult as well as juvenile interests. These include royal family and coronation commemoratives, images of politicians and celebrities, exhibition and holiday souvenirs, Sunday school and temperance sentiments, and mythical and chinoiserie fantasies. (*Examples of two of these subjects, also available from Seekers, are pictured in the footnote following this article.)

Noel Riley's research came to two striking conclusions regarding the manufacturing process: the relative anonymity of manufacturers and the surprising amount of original source material used to create the patterns.

We know that almost every major 19th century pottery produced this class of goods. However research has identified only around sixty potters. There is no doubt that a great many more potters engaged in production of these wares. However, manufacturers had multiple reasons to remain anonymous in this aspect of their production. The pieces were neither highly regarded, nor carried in prestigious sales venues. Then of course there was the inconvenient matter of copyright issues. As we have noted above, few potters generated original artwork for these wares. The general practice was to copy from whatever presented itself with just enough variation to escape accusations of copyright infringement. In some instances, copyrights were entirely ignored, possibly based on the assumption that the wares were too humble to warrant litigation.

References

Posted By: Mark

Posted on: 2010-10-25 01:04:03

Featured Item:

Feldspathic Stoneware Tall Pot

Over several years of antiques shows in Richmond, Virginia, Seekers Antiques has established a network of customers who have become good friends. In turn, we have been shown the wonderful architecture of the city and surrounding area through the eyes of the natives. One of the treats Richmond has to offer is multiple lessons in Neoclassicism. Examples range from the sacred space of Robert Mills 1812 Monumental Church to John Russell Pope's 1917 train station, a twentieth century machine age variation on Neoclassicism. We never tire of staring -- like American tourists at these magnificent structures.

Monumental Church as shown on an 1830's historical transfer dessert plate by J&J Jackson, /products/3679

John Russell Pope's Broad Street 1917 Train Station, Richmond, Virginia (Wikipedia Image, U.S. National Register of Historic Places)

One of the shows Seekers Antiques has participated in takes place in Pope's former train station (now a science museum). This has allowed us to become more familiar with the raw grandeur of this structure. Many will be more familiar with the similar National Gallery in Washington, D.C., also a Pope design. With both strucures, Pope takes a severe, no-nonsense point of view and in so doing creates an inspiring, if not intimidating magnificence. In the same way, some unknown early nineteenth century English potter created the feldspathic tall pot which is the subject of this month's featured item. Both are variations in the Neoclassical style. Both can stop me in my tracks. I hope that in this piece, I convey some sense of my reverence for Neoclassicism and of course, this piece.

Dimensions: Height 8 1/2 in., Width 12 in.

Dates: ca. 1810

Price: $1250.00

The Piece---- Adjectives describing this pot range from graceful and classical to architectural or monumental, from clean to Spartan, even severe. Whichever set you prefer, it can not be denied --- this is an impressive piece. The stone-like surface, contrasting glossy teal green enamel outline, vertical stance and imposing scale set it apart in the typically cozy world of English teapots. Even the decoration has been made subservient to the imposing scale.

The Piece---- Adjectives describing this pot range from graceful and classical to architectural or monumental, from clean to Spartan, even severe. Whichever set you prefer, it can not be denied --- this is an impressive piece. The stone-like surface, contrasting glossy teal green enamel outline, vertical stance and imposing scale set it apart in the typically cozy world of English teapots. Even the decoration has been made subservient to the imposing scale.

In considering this piece, shape is a key factor. This piece is derived from the elegant late eighteenth century oval silver shape --- later christened "Old Oval" by the Spode potters. It is no stretch to view this piece in architectural terms as two oval voids stacked on top of each other with added lid and spout components. The minimal decoration underscores this sense of independent components,as does the contrast of undecorated surfaces with vertically ribbed expanses (referred to as reeding). High gloss teal green enamel striping finishes the statement profiling each section and part. Even the rim of the pot has the appearance of a separate band.

Our un-identified potter however can not hold totally to his disciplined program of Spartan economies. He makes two concessions to the frivolous, a perfect floral form knop and some extra curls approximating joins in the handle. After all, all work and no play. . . . . .

. .

Feldspathic Stoneware

In understanding this pot, or any example of English ceramics, one starts with the clay body --- in this case, Feldspathic Stoneware. As the name implies, this is a stoneware body containing feldspar. A technical discussion of the dual roles of feldspar in the production of pottery would involve discussion of manufacturing techniques and the various uses of feldspar. This might be fascinating for all the renaissance men (and women) reading this item, but we feel goes beyond the scope of this piece. We feel a definition of feldspathic stoneware as it relates to the marketplace is more relevant here.

Given the fact that most of us can not perform chemical analysis of English ceramics with our fingertips, the market has evolved its own definition of Feldspathic Stoneware. Feldspathic stoneware is seen as a strong, dense, hard, white ceramic body posssessing a unique porcelain-like sense of fragility. One of feldspar's attributes is the ability to produce an occasional degree of translucence similar to porcelain. When present, this adds to that sense of fragility and preciousness. The market acknowledges this on again, off again translucence --- but puts no special premium on it one way or another. Feldspathic stoneware is a dry body stoneware, a class of (usually) unglazed bodies which includes jasper and basalt among others. While unglazed, the matte surface, compared by some to white chocolate, is often accented by simple outline decoration in glossy enamel.

The occurence of feldspathic stoneware is stongly linked with a specific style, Neoclassicism. Diana Edwards Roussel in The Castleford Pottery 1790-1821 * dates the start of production around 1795, well after the movement had become established (see below). She notes that "after about 1815, as the neo-classical movement within the decorative arts began to decline, so did the popularity of the feldspathic stonewares, jaspers and blackwares, which were gradually replaced by porcelains and ironstones."

The occurence of feldspathic stoneware is stongly linked with a specific style, Neoclassicism. Diana Edwards Roussel in The Castleford Pottery 1790-1821 * dates the start of production around 1795, well after the movement had become established (see below). She notes that "after about 1815, as the neo-classical movement within the decorative arts began to decline, so did the popularity of the feldspathic stonewares, jaspers and blackwares, which were gradually replaced by porcelains and ironstones."

Teapots and Neoclassicism --- There were no teapots in Rome.

Teapots and Neoclassicism --- There were no teapots in Rome.

This brings us to the Neoclassical movement. Neoclassicism is the expression in the arts of the great change sweeping the world from around the time of the American Revolution through the early nineteenth century. This change was precipitated in large part by the new wealth generated through manufacturing and commerce. This new wealth, more urban in character was also more social; this era saw the advent of coffeehouse culture. Value was put on the free exchange of ideas, especially scientific advances and the resulting new technologies. This intellectual realm also included the exploration and re-discovery of the ancient world through archaeology and the examination and systematic cataloging of extant ruins. Publication of their findings by both French and English scholars caught the imagination of an international public. This fascination permeated life from architecture to dress, landscape and city planning, even influencing emerging new governments. Nor did household decoration escape the obsession. However there were no teapots in Rome.

Robin Emerson in his catalog British Teapots & Tea Drinking, 1700-1850, Illustrated from the Twining Teapot Gallery, Norwich Castle Museum devotes two chapters to the impact of classical design on the teapot in both pottery and porcelain. Emerson maintains that the Neoclassical taste was firmly established by 1765. He writes from an appropriately English point of view, pointing out the works of 'Athenian' Stuart, the Adam brothers and William Chambers. He points out the clever transformation of rococco scrollwork into Greek and Roman ornament. He also points out the use of matt color on both walls and furnishings which transferred to the tea table in unglazed, dry body wares. Obviously Feldspathic Stoneware with its marble-like matt surface was especially suited to this new taste. There are no surprises here for anyone with a casual acquaintance with European design history.

Robin Emerson in his catalog British Teapots & Tea Drinking, 1700-1850, Illustrated from the Twining Teapot Gallery, Norwich Castle Museum devotes two chapters to the impact of classical design on the teapot in both pottery and porcelain. Emerson maintains that the Neoclassical taste was firmly established by 1765. He writes from an appropriately English point of view, pointing out the works of 'Athenian' Stuart, the Adam brothers and William Chambers. He points out the clever transformation of rococco scrollwork into Greek and Roman ornament. He also points out the use of matt color on both walls and furnishings which transferred to the tea table in unglazed, dry body wares. Obviously Feldspathic Stoneware with its marble-like matt surface was especially suited to this new taste. There are no surprises here for anyone with a casual acquaintance with European design history.

The surprise (and Emerson's great insight) has to do with that favorite obsession we referred to earlier, the pursuit of all things scientific and the attendant technology. It is the confluence of new technologies with fashion which precipitated tea wares in the Neoclassical taste.

First there was the experimentation and development of new ceramic bodies which had been catalysed by Josiah Wedgwood's financial success in developing (and marketing) basalt, creamware and jasper. Robin Emerson feels the Turners may have been responsible for developing the feldspathic stone body in the 1780's. Emerson notes however that Simeon Shaw, writing in the early 19th century attributed introduction to Chetham and Wooley around 1795.

(Left) Feldspathic Creamer by Turner.

(Right) Feldspathic Creamer attributed to Cheatham and Wooley.

More importantly, Emerson points to the invention of Sheffield Plate which had become a force in the marketplace by 1760. This was the technology which would have the greatest impact on the look of Neoclassical tea wares. This new technology suddenly made silver (or a silver variant) accessible to a much broader public. There was only one challenge. Sheffield plate involved production from large sheets of silver. Given the awkwardness of producing traditional spherical tepot shapes from sheet silver, a new form based on box shapes and angles was developed. This new form lent itself to forms based on classical columns, friezes and plinths and the accompanying decoration, the vocabulary of Neoclassicism.

This may seem irrelevant in a discussion of ceramics, however ceramic shapes often develop from silver shapes. One of the new ceramic shapes originating around 1790 was based on a new Neoclassical silver oval shape of ten years earlier. As we mentioned earlier, this shape came to be known as the "Old Oval" shape. This is the shape associated with our tall pot.

The Manufacturer Question.

An Anthology of British Teapots by Phillip Miller and Michael Berthoud is one of our go-to references when tracking any piece of teaware.

Primarily a picture book divided into general categories, the book serves as a sort of field guide to teapots. While a mate to our pot is not included, we found a number of teapots close enough in shape, decoration, handles or knops to suggest that they are the products of the same manufacturer.** This group included examples executed in basalt and lustre glazed earthenware as well as white (we assume feldspathic) stoneware. The only marked examples in this group are by J. Glass of Hanley.

Diana Edwards and Rodney Hampson in English Dry-Bodied Stoneware, Wedgwood and Contemporary Manufacturers, 1774-1830 give a listing for various John Glass, Hanley partnerships from 1784 through 1834 noting production in both basalt and white smear-glazed teawares. (We have also owned a feldspathic stoneware teapot related to the marked basalt examples.) All of these partnerships seem to have been in close proximity to each other, if not the same location.

While we have far too little evidence for any sort of firm attribution, the picture emerges of a potter responsible for a sizable production of considerable variety, finesse in production, and sophistication in design. One can speculate that it must have been a potter of some longevity. J. Glass may indeed fit this bill, but a conclusion awaits new references or the serendipitous discovery of a marked, but previously unrecorded example--a kind of ceramic missing link. It is out there someplace!

One final look at this piece may shed light on our mystery potter or at least the pot itself. We are back to the design. Decoration here is minimal in the extreme, even by the chaste standards of Neoclassicism. We see the argument here as two sided. Was this minimal decoration an effort to hold costs to a minimum or was our potter creating product for the more austere Neoclassicists of the continent?

The validity of the price argument seems obvious: less sprigwork, less detail, less time, labor and loss, less investment, more profit --- good British manufacturing sense.

Ledoux 1788 Gatehouse, Parc Monceau, Paris (Wikipedia Images)

Schinkel 1835 Elisabethkirche, Berlin (Wikipedia Images)

However as we noted above, Neoclassicism was not confined to the British Isles. A product made for a continental audience cannot be dismissed. The British were making ceramics for the entire world. The Neoclassical style was already established in France prior to the Revolution. One need only look at the cool, restrained Neoclassical architecture of Charles Nicholas Ledoux's 1788 gatehouse off the Parc Monceau in Paris. At Chaux, Ledoux adapted Neoclassical forms for an entire town purpose-built on a salt refining site. Just as British manufacturers adapted Neoclassical style to the table, Ledoux adapted the style to modern French life. One could also look to German architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel for architectural variation corresponding to our pot in majesty and austerity. In comparison to these continental masters, British Neoclassicism with its playful putti and scrollwork seems frivolous. Likewise, other Feldspathic tea wares seem frivolous in comparison to this pot. Perhaps this design was conceived with a continental market in mind. This would indicate a potter well established and of a higher degree of sophistication than most.

Tall Pots, Teapots, Coffee Pots

Tall Pots, Teapots, Coffee Pots

Before leaving this discussion, we feel some mention of the teapot / coffee pot argument must be addressed. That is to say, when considering tall pots, use always comes into question. Henry Sandon, Coffee Pots and Teapots For The Collector maintains the tall pot shape was for coffee. He backs this up with examples of eighteenth century porcelain. Sandon also states that ceramic coffee pots tend to disappear after 1800, metal being the preferred medium. As far as feldspathic stoneware pots are concerned, our experience would seem to agree with Sandon. This is the third feldspathic stoneware tall pot we have encountered in the last twenty years. Regarding the teapot /coffee pot issue, given the fact that we are familiar with the teapot corresponding to this tall pot (from Miller and Berthoud above), this indeed may be a coffee pot.

Conclusion

Conclusion

Exploration of the world of antiques, architecture and art never fails to satisfy. From the sacred space of Robert Mill's Monumental Church to the machine-age grandeur of John Russell Pope's train station to the cool, spare sophistication of the Ledoux gatehouse off the Parc Monceau in Paris, one sees a continuous strand, Neoclassicism and the pursuit of knowledge which was so much a part of the movement ------- and in this one stoneware teapot, one sees it all.

Cheers, Mark

*Diana Edwards Roussel The Castleford Pottery 1790-1821; When this book was published in 1982, many collectors referred to all feldspathic stoneware as Castleford. One of the points which the book made was that Castleford was a pottery which made feldspathic stoneware, but that there were many other potteries which produced the ware as well.

** Phillp Miller and Michael Berthoud An Anthology of British Teapots; Miller and Berthoud illustrate four teapots which share the distincitive reeded panel treatment of our teapot (p. 122, Plts 727,729,731; p. 125, plt. 747). There are twenty-four pots in the larger group of related pots including the J. Glass pots (p.122-125)

Additional Feldspathic Stoneware pieces in Seekers current stock:

Feldspathic Stoneware Sugar Bowl and Lid, Possibly Leeds Pottery /products/2131

Feldspathic Stoneware Creamer, Attributed to Cheatham & Wooley /products/2278

Other examples of feldspathic stoneware illustrated above, from Seekers file photos

Sources

Robin Emerson; British Teapots & Tea Drinking, 1700-1850, Illustrated from the Twining Teapot Gallery, Norwich Castle: 1992; ISBN 0 11 701509 1;HMSO Publications, PO Box 276, London, SW8 5DT, UK

Phillip Milller and Michael Berthoud An Anthology of British Teapots; 1985; ISBN 0 9507103 4 2;

Micawber Publications, Bridgnorth, Shropshire WV164DR, UK

Diana Edwards and Rodney Hampson; English Dry-Bodied Stoneware, Wedgwood and Contemporary Manufacturers 1774-1830; 1998; ISBN 1 85149 288 7; Antique Collectors' Club Ltd., Woodbridge, Suffolk IP12 1DS UK

Henry Sandon; Coffee Pots and Teapots For The Collector; 1973; ISBN 0 8512 910 0;

John Bartholomew and Son Ltd., Edinburgh EH91TA

Diana Edwards Roussel; The Castleford Pottery 1790-1821; 1982; ISBN 0 901869 12 0; Wakefield Histoircal Publications; Londonderry Press, Bellmont, Massachusetts, 02178

Barry Bergdoll; Oxford History of Art, European Architecture 1750-1890; 2000; ISBN-13: 978-0-19-284222-0 ISBN 0-19-284222-6; Oxford University Press, Oxford OX2 6DP UK

Michael Snodin; Karl Friedrich Schinkel: A Universal Man; 1991; Published to coincide with the exhibition of the same name, The Victoria and Albert Museum, London, 1991; ISBN 0-300-05166-2; Yale University Press, New Haven and London

« Prev

Next »