Posted By: Tim

Posted on: 2011-10-05 13:46:50

Featured Item:

"Bacchanalian Dance" Jug by Charles Meigh

Quite apart from their tactile, sculptural appeal, English relief molded jugs, produced in profusion in the last three quarters of the nineteenth century, yield some interesting insights to those who consider them carefully. Through various examples one can trace the progression of style trends from the neoclassical, to rococo and gothic revivals , and on to Japanese-inspired aesthetic movement designs. From the elaborately detailed designs of the century's first half to the later trend to simplify forms in the interest of function and cleanliness, they reflect a desire to provide a quality product for the expanding middle class market. Most of all, the variety of patterns result from the potter's urge to flex his muscles and to exercise the potential of developing manufacturing techniques.

Now and then a jug will provide not only these broad insights, but also a look at the personal interests of its maker. One such jug is Charles Meigh's 1844 "Bacchanalian Dance."

Dimensions: Height 7 in.

Mark: Pad Mark

Dates: Registered September, 1844

Price: $425.00 each

.

A Connoisseur Potter

A Connoisseur Potter

In his 1829 History of the Staffordshire Potteries, Simeon Shaw expresses admiration for C. Meigh, Esq., second generation of his family's proprietorship of the Old Hall pottery works. Meigh, he says,

is esteemed for his firmness and decision of character, the arts have not a more liberal patron, for his means; nor the poor and defenceless a more firm protector. His modesty and candour are of general notice; and his friendship has never been known to be affected by the vicissitudes of fortune; nor has his kindness been withheld when the suffering could be alleviated (1).

Among these virtues it is his patronage of the arts that is of interest to us. In his Relief Molded Jugs 1820-1900, R. K. Henrywood further cites an 1846 description of Meigh's own collection of pictures, numbering over 200 examples of the works of admired artists (2). His artistic sophistication is demonstrated in his painstaking treatment of gothic architectural detail in his "Apostles" jug and in the complex elements of his depiction of Neptune's wife Amphitrite.

But even more revealing of his reverence for the masters is his jug celebrating the liberating, inebriating effects of wine.

In his "Bacchanalian Dance" jug, Meigh chose to recreate in relief two paintings by seventeenth century masters--Nicholas Poussin and Peter Paul Rubens. To provide a form to present these tableaus without distortion he created a most original shape centering on a cylinder with a straight sided profile. Around this band he wraps the two compositions, one to a side. Above and below the jug swells with a bounty of grape vines, forming an appropriately exuberant frame for the works of the baroque masters.

.

The Poussin painting is today known by the unwieldy title "Bacchanalian Revel Before a Term of Pan."

Eliminating only one figure from the elaborate composition, Meigh's modeler captures a group of three dancing adults and two putti on the left, and on the right, before a column-form statue (herm) of Pan, a female defending her fallen cohort against the advances of a satyr. With surprising detail--preserved even in smaller sizes of the jug--we see grape leaves in one dancer's hand and the small jug raised to strike the amorous satyr.

Henrywood quite reasonably suggests that the jug is based on an engraved reproduction of the painting rather than the original (3). Meigh, however, could have familiarized himself with the painting by journeying to London. It had entered the collection of the young National Gallery in 1829. Either Meigh or the engraver made one modification in the interest of modesty. A loincloth is provided for the middle dancer of the right hand group whose exposed buttocks feature prominently in Poussin's depiction.

The Rubens Side

The Rubens SideTurning the jug around, One is confronted with a less joyous view of inebriation. An old man, whose flabby and corpulent nakedness reveals the effects of long-term dissipation, is helped along by two satyrs and a group of revelers. They seem to be in an advanced drunken stupor. This is Silenus who was entrusted by Zeus with the jobs of guardian and tutor of Bacchus, the infant god of wine. A bit of a prophet, Silenus was mostly known as a drunk and is most often depicted propped up by his drinking buddies or about to fall off the back of a donkey.

Bad Habits Passed Down

Bad Habits Passed DownI am reminded of Silenus and his two supporters by one of the charming putti groups designed in the eighteenth century for Josiah Wedgwood by the noblewoman and amateur artist Diana Beauclerk (shown here on an early nineteenth century glazed caneware jug currently available from Seekers).

This is probably not tiny Silenus, but baby Bacchus--the pinecone tipped staff he holds is the wine god's symbol. But young Baccchus's tutor certainly taught him to drink, and here he almost duplicated his mentor's pose. Obviously aging flab is replaced by childish chubbiness; the humor is a good deal more refined; the style is a charming rococo version of the classical subject; and the tone is naughty at worst. Still, I think a hint of old Silenus remains.

More Silenus(es)

More Silenus(es)Charles Meigh was not entirely original in adapting Silenus in the relief decoration of a jug. Minton had produced a simpler treatment in 1831 that clearly seems based (more roughly) on Rubens's three central figures. Much earlier is a seventeenth century German ivory and silver tankard bearing a detailed version of the scene, now in the collection of the Art Gallery of Toronto.

Meigh produced his own variations on his "Bacchanalian Dance." A two-color parian version is shown below as well as an adaptation in a mug form for which Meigh won an award from the Society of Arts in 1847. (Note that here Silenus has been given a sort of kilt.)

Finally, the enduring charms of old Silenus are carried into the twenty first century by this thermal version bearing one of Van Dyck's adaptations of the scene.

Acknowledgements and Notes

Acknowledgements and NotesIt seems pretentious to attach a dedication to an essay as slight as this, but I cannot pass up the opportunity to acknowledge the influence of our good friend Kathy Hughes. At her Tudor house gallery in Charlotte, at shows throughout the eastern United States, and most importantly through her publications--A Collector's Guide to Nineteenth-Century Jugs, Kathy taught a great many Americans to love the English relief-molded jug.

R. K. Henrywood provides a full documentation of the sources of "Bacchanalian Dance" in his general history of these jugs. The narrative of his book is complimented by the convenience of Hughes's books which serve as a sort of a field identification guide for the jug watcher. Unfortunately, these books are not easy to acquire today.

Henrywood, R. K. Relief Moulded Jugs 1820-1900. Woodbridge, Antique Collectors' Club 1984.

Hughes, Kathy. A Collector's Guide to Nineteenth-Century Jugs. London, Routledge & Kegan Paul 1985.

Hughes, Kathy. A Collector's Guide to Nineteenth-Century Jugs, Vol. II. Dallas, Taylor Publishing Company, 1991.

(1) Shaw, Simeon. History of the Staffordshire Potteries. New York, Praeger Publishers 1970 (reprint). Pg. 44-5. (Henrywood quotes this passage in part.)

(2) Henrywood, pg. 108.

(3) Henrywood, pg. 110.

Posted By: Mark

Posted on: 2011-07-31 00:19:41

Featured Item:

Red Transferware Dinner Plate

Edward and George Phillips "Polish Views"

"A Tear For Poland"

Earlier this year, some of us caught the excitement of change as we watched it catch hold in the eastern Mediterranean and Africa. What an amazing phenomenon, this movement mounted by citizens on cell phones, Facebook, Twitter and the internet and the revolution they staged from within. As freedom loving people, we celebrate their victories while wondering how they will conquer the challenges they have brought upon themselves.

Date: 1830's (George Phillips 1834-1848)

Price: $225.00

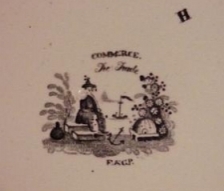

Now and then when we first encounter a piece of transferware, we are totally puzzled. This is one such case. What initially appears to be simply another piece of romantic tableware in fact reveals an enigmatic scene--a man and woman sit in a park surrounding an elaborate onion domed palace. Typical enough, except the man appears to be weeping into his hands. Closer examination reveals a horseman wearing a distinctive, possibly military cap rounding the corner in the middle distance. Turning to the backstamp we find an innocuous enough pattern name, "Polish Views," but also a scene title that clearly indicates that something darker is involved, "A Tear for Poland." Transferware authority Dick Henrywood tells us that Phillip's "Polish Views" series includes these additional scenes: "Patriot's Departure," "Polish Prisoner," "The Enquiry," "The Messenger," "Wearied Poles," and "Wounded Poles."(1) These are hardly the subjects one expects to find in a pattern based merely on regional scenery.

Now and then when we first encounter a piece of transferware, we are totally puzzled. This is one such case. What initially appears to be simply another piece of romantic tableware in fact reveals an enigmatic scene--a man and woman sit in a park surrounding an elaborate onion domed palace. Typical enough, except the man appears to be weeping into his hands. Closer examination reveals a horseman wearing a distinctive, possibly military cap rounding the corner in the middle distance. Turning to the backstamp we find an innocuous enough pattern name, "Polish Views," but also a scene title that clearly indicates that something darker is involved, "A Tear for Poland." Transferware authority Dick Henrywood tells us that Phillip's "Polish Views" series includes these additional scenes: "Patriot's Departure," "Polish Prisoner," "The Enquiry," "The Messenger," "Wearied Poles," and "Wounded Poles."(1) These are hardly the subjects one expects to find in a pattern based merely on regional scenery. And the rest of Europe . . . grieved. The Poles did not grieve alone for their lost homeland. The same jubilation which had met the news of the American successes in the 1770's turned to lamentation with the news of the annihilation of the Polish state in 1795. Zamoyski details the expression of this widespread despair in the arts. Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote of "murdered Hope," in a sonnet bewailing Polish military leader Kosciuszko's defeat. In the public imagination, the Polish patriot took on a hallowed status not unlike Washington, a paragon of Spartan virtue. Dwelling on the Polish freedom fighters capture, the Scots poet Thomas Campbell spoke for the public in his lines: "Hope, for a season, bade the world farewell, / And Freedom shriek'd -- as Kosciuszko fell!" George Galloway, another Scottish poet published a book of poetry around the theme of Poland, The Tears of Poland (Edinburgh, 1795) (4). In France even Jacques-Louis David caught the Polish mania with his design for the appropriate dress for delegates to the French Convention in 1794-- a combination of pseudo Roman garb topped off with the traditional Polish konfederatka cap.(5) The heroic aspect of the Polish struggle against overwhelming odds provided grist for the public imagination, stirring outrage in the cause of martyred innocence.

And the rest of Europe . . . grieved. The Poles did not grieve alone for their lost homeland. The same jubilation which had met the news of the American successes in the 1770's turned to lamentation with the news of the annihilation of the Polish state in 1795. Zamoyski details the expression of this widespread despair in the arts. Samuel Taylor Coleridge wrote of "murdered Hope," in a sonnet bewailing Polish military leader Kosciuszko's defeat. In the public imagination, the Polish patriot took on a hallowed status not unlike Washington, a paragon of Spartan virtue. Dwelling on the Polish freedom fighters capture, the Scots poet Thomas Campbell spoke for the public in his lines: "Hope, for a season, bade the world farewell, / And Freedom shriek'd -- as Kosciuszko fell!" George Galloway, another Scottish poet published a book of poetry around the theme of Poland, The Tears of Poland (Edinburgh, 1795) (4). In France even Jacques-Louis David caught the Polish mania with his design for the appropriate dress for delegates to the French Convention in 1794-- a combination of pseudo Roman garb topped off with the traditional Polish konfederatka cap.(5) The heroic aspect of the Polish struggle against overwhelming odds provided grist for the public imagination, stirring outrage in the cause of martyred innocence.

With the onset of the nineteenth century and the frustration of many of the hopes for change, revolutionary zeal gave way to the introspection and frequent despair of the Romantic movement. In preceding decades great change was dreamed of and achieved. In this new age, one could only dream of the feats of other days with no hope of impacting the structure of power which had been re-established over Europe with the end of the Napoleonic wars. Throughout Europe, a surfeit of out-of-work soldiers struggled to return to the boredom of everyday life after the glories and excitement of war. Furthermore, a generation raised to dream of nothing but the excitement of service now felt cheated and disillusioned with the advent of peace. Together these segments only added to a general sense of silent resignation and despondency.

With the onset of the nineteenth century and the frustration of many of the hopes for change, revolutionary zeal gave way to the introspection and frequent despair of the Romantic movement. In preceding decades great change was dreamed of and achieved. In this new age, one could only dream of the feats of other days with no hope of impacting the structure of power which had been re-established over Europe with the end of the Napoleonic wars. Throughout Europe, a surfeit of out-of-work soldiers struggled to return to the boredom of everyday life after the glories and excitement of war. Furthermore, a generation raised to dream of nothing but the excitement of service now felt cheated and disillusioned with the advent of peace. Together these segments only added to a general sense of silent resignation and despondency. The shift in mood was particularly pertinent to Poland. Poland's fate continued to be subject to foreign masters, first Napoleon, later Czar Alexander I, Catherine's grandson, who saw it as his mission to re-establish the noble state. However, as Alexander saw himself as head, conflicts soon developed as the Poles started to strive for self determination. Alexander pre-empted any sense of independence generating a state of constant tension, conflict and of hopelessness. In 1830 yet another uprising was defeated. In Paris Frederic Chopin expressed his anxiety for friends and family back in Warsaw, generating one of the supreme Romantic expressions of Polish concern and despair. This was his Scherzo in B minor Op. 20 and his "Revolutionary" Etude, in C minor, Op. 10, No. 12.

The shift in mood was particularly pertinent to Poland. Poland's fate continued to be subject to foreign masters, first Napoleon, later Czar Alexander I, Catherine's grandson, who saw it as his mission to re-establish the noble state. However, as Alexander saw himself as head, conflicts soon developed as the Poles started to strive for self determination. Alexander pre-empted any sense of independence generating a state of constant tension, conflict and of hopelessness. In 1830 yet another uprising was defeated. In Paris Frederic Chopin expressed his anxiety for friends and family back in Warsaw, generating one of the supreme Romantic expressions of Polish concern and despair. This was his Scherzo in B minor Op. 20 and his "Revolutionary" Etude, in C minor, Op. 10, No. 12.  This sense of a lost cause provides the immediate context for the titles in Phillips' "Polish Views" series with their references to prisoners, wounds, weariness and tears. This is a pattern that reflects not only the specific Polish cause, but also the larger Romantic disposition.

This sense of a lost cause provides the immediate context for the titles in Phillips' "Polish Views" series with their references to prisoners, wounds, weariness and tears. This is a pattern that reflects not only the specific Polish cause, but also the larger Romantic disposition.

Sources

Coysh, A.W. Blue-Printed Earthenware 1800-1850 . David & Charles Inc., North Pomfret, Vermont, 1980

« Prev

Next »